Renewable Energy Solutions Developing Nations Of course. Here’s a comprehensive overview of the challenges, opportunities, key technologies, and strategies for developing renewable energy solutions in developing nations.

The Core Challenge: The Energy Poverty Trap

Many developing nations are caught in a cycle:

- Lack of Access: Over 700 million people globally lack access to electricity, predominantly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia.

- High Cost of Fossil Fuels: Importing diesel and coal consumes foreign reserves and exposes nations to volatile global prices.

- Unreliable Grids: Existing grids are often underdeveloped, prone to blackouts, and don’t reach remote rural areas.

- Upfront Capital Costs: While renewable energy has low operating costs, the initial investment for solar farms, wind turbines, or mini-grids is high.

- Renewable energy offers a path to break this trap, providing clean, reliable, and increasingly affordable power.

Key Renewable Energy Solutions for Developing Nations

The “right” solution depends heavily on local geography, resources, and population density.

Solar Power (The Frontrunner)

Technologies:

- Utility-Scale Solar Farms: Large installations feeding power into the main grid. Ideal for sunny, arid regions.

- Solar Mini-Grids: Small-scale localized grids powered by solar panels and batteries, perfect for villages and small towns beyond the main grid.

- Solar Home Systems (SHS): Single-panel systems powering lights, phone charging, and small appliances for individual households. Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG) financing has revolutionized this market.

- Advantages: Plummeting costs, modular and scalable, quick to deploy, vast solar potential in most developing nations.

Wind Power

Technologies:

- Onshore Wind Farms: Effective in regions with consistent wind resources (e.g., coastal areas, plains, Eastern Africa).

- Small-Scale Wind Turbines: Can be used for community-level power or water pumping.

- Advantages: Cost-competitive, can be combined with solar (hybrid systems) for more consistent power.

Hydropower

Technologies:

- Large-Scale Hydropower: Provides massive baseload power but has high environmental and social impacts (displacement, ecosystem damage).

- Mini and Micro-Hydropower: Small run-of-river systems that have minimal environmental impact and are excellent for powering remote, hilly communities with flowing water sources.

- Advantages: Reliable, predictable, low operating costs, provides energy storage (in large dams).

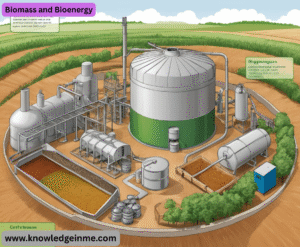

Biomass and Bioenergy

Technologies:

- Advanced Biofuels: From agricultural waste (e.g., sugarcane bagasse, rice husks).

- Biogas Digesters: Convert animal and plant waste into cooking gas and fertilizer, addressing indoor air pollution from wood fires.

- Advantages: Utilizes local waste products, provides cleaner cooking solutions, creates circular economies.

Geothermal Power

- Application: Highly location-specific but offers immense, reliable baseload power. A major opportunity for countries along the East African Rift Valley (e.g., Kenya, Ethiopia).

- Advantages: Not weather-dependent, high capacity factor, stable power output.

Major Opportunities and Benefits

- Leapfrogging the Grid: Just as many nations skipped landline phones for mobile networks, they can bypass centralized, fossil-fuel-powered grids for decentralized renewable systems and smart mini-grids.

- Economic Development: Reliable energy powers businesses, agro-processing, and industries, creating jobs and boosting local economies.

- Energy Security: Reduces dependence on expensive and volatile fossil fuel imports, keeping wealth within the country.

- Climate Resilience and SDGs: Directly contributes to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) like SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), while also improving health (by reducing indoor air pollution), education (lighting for studying), and gender equality (freeing women and girls from fuel collection duties).

- Job Creation: Creates local jobs in installation, maintenance, and management of renewable systems.

Critical Barriers and Challenges

- Financing and Investment: The high upfront cost is the single biggest barrier. International investors often perceive high risk.

- Policy and Regulatory Uncertainty: Lack of clear policies, transparent permitting, and supportive regulations can stall projects.

- Grid Infrastructure: Weak and outdated transmission grids cannot always handle intermittent renewable sources like solar and wind.

- Technical Capacity: A shortage of local engineers, technicians, and project managers to build and maintain systems.

- Currency and Off-Taker Risk: Uncertainty about being paid by the state-owned utility (the off-taker) and currency fluctuation risks deter foreign investment.

Strategies for Successful Implementation

Innovative Business and Financing Models:

- Pay-As-You-Go (PAYG): Allows users to pay for solar systems in small installments via mobile money, making them affordable.

- Blended Finance: Using public or philanthropic funds to de-risk projects and attract much larger private investment.

- Green Bonds: Issuing bonds specifically for climate-friendly projects.

Strong Policy Frameworks:

- Clear National Energy Plans: Setting ambitious but achievable renewable energy targets.

- Supportive Regulations: Implementing feed-in tariffs, tax incentives, and simplified permitting processes.

- Standardized Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs): Reducing negotiation time and cost for independent power producers.

Technology and Capacity Building:

- Technology Transfer: Partnerships with developed nations and international companies.

- Vocational Training: Investing in local technical colleges and training programs to build a skilled workforce.

- Community Ownership: Involving local communities in project planning and ownership increases acceptance and long-term sustainability.

Focus on Hybrid and Decentralized Systems:

- Solar-Diesel Hybrids: Reducing fuel costs for existing diesel mini-grids.

- Renewable-Battery Mini-Grids: Providing 24/7 reliable power to communities, fostering local enterprise.

Real-World Success Stories

- Kenya: A world leader in geothermal power and has one of the highest rates of solar SYS ownership in Africa. The Lake Turkana Wind Power project is one of the largest in Africa.

- Bangladesh: A global pioneer in solar home systems, bringing electricity to millions of rural households through its Infrastructure Development Company Limited (IDCOL) program.

- Rwanda: Aggressively developing solar mini-grids and the first African country to launch a domestic Green Bond to finance environmental projects.

- Morocco: Home to the Noor Ouarzazate complex, one of the world’s largest concentrated solar power plants, powering its grid and reducing imports.

The Digital Enabler: Technology’s Role in Acceleration

The rise of digitalization is a game-changer, making renewable deployment faster, smarter, and more efficient.

- Internet of Things (IoT): Smart meters and sensors in mini-grids allow for real-time monitoring of energy production and consumption, enabling dynamic pricing and efficient load management. They can also detect faults before they cause outages.

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Big Data: AI can forecast solar and wind generation based on weather data, optimizing the operation of hybrid systems (e.g., deciding when to switch to battery storage or a backup generator). It can also analyze consumption patterns to design better-suited systems.

- Blockchain: Can be used to create peer-to-peer energy trading platforms within a mini-grid, allowing households with excess solar power to sell directly to their neighbors, creating a local energy market.

- Mobile Money: As mentioned with PAYG, platforms like M-Pesa in Kenya are fundamental. They facilitate seamless micropayments for energy services, building a credit history for unbanked populations.

The Social Dimension: More Than Just Megawatts

The success of renewable energy projects is often determined by social factors, not just technical ones.

- Gender Inclusion: Energy access disproportionately benefits women and girls. It reduces the time spent on fuel collection (often a female task), improves safety with street lighting, and opens up opportunities for women-led enterprises. Projects designed with gender inclusivity in mind are more sustainable and have a broader impact.

- Productive Use of Energy (PUE): This is a critical concept. Simply providing power for lights and phones has limited economic impact. The key is to stimulate demand by powering appliances that generate income.

- Examples: Solar-powered water pumps for irrigation, refrigerators for cold storage of fish and produce, electric mills for grinding grain, welding machines, and carpentry tools.

- Strategy: Successful projects often bundle energy access with financing for these productive appliances, ensuring the community can leverage the power for economic growth.

- Land Rights and Community Engagement: Large-scale projects require land. Navigating traditional land tenure systems and ensuring transparent negotiations with communities is essential to avoid conflict. Community co-ownership models, where locals have a stake in the project’s revenue, foster a sense of ownership and long-term viability.

The Geopolitical and Supply Chain Landscape

The global rush for renewables creates new dependencies and opportunities.

- Critical Minerals: The energy transition requires vast amounts of minerals like lithium, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements. Many developing nations are rich in these resources (e.g., the Democratic Republic of Congo for cobalt, Chile for lithium). This presents a massive economic opportunity but also risks of the “resource curse” if not managed with good governance and policies that promote local value-addition (e.g., manufacturing battery components locally instead of just exporting raw ore).

- China’s Dominant Role: China is the world’s leading manufacturer of solar panels, batteries, and other renewable components. This provides developing nations with affordable technology. However, it also creates a dependency, and concerns about debt sustainability have been raised regarding Chinese infrastructure loans.

- Onshoring and Friend-Shoring: Following global supply chain disruptions, there is a push in the West to build manufacturing capacity outside of China. This could present a major industrial opportunity for developing nations with stable policies and low labor costs to become hubs for component manufacturing for both domestic and regional markets.

A Deeper Look at Financial Innovation

Beyond blended finance, other sophisticated models are emerging.

- Results-Based Financing (RBF): Donors or governments provide funding only after pre-agreed results are verified (e.g., number of connections made, hours of power delivered). This shifts focus from building infrastructure to delivering actual services.

- Carbon Finance: Renewable energy projects generate carbon credits by displacing fossil fuels. These credits can be sold on international carbon markets, providing an additional revenue stream that improves project economics.

- Securitization: Bundling many small, performing assets (like thousands of PAYG solar loans) into a single financial product that can be sold to institutional investors. This frees up capital for the original company to lend again, dramatically scaling up access.

The “Just Transition” Framework

This concept, often discussed in the context of phasing out coal, is equally relevant here. It ensures the energy transition is fair and inclusive.

- Focus on Fossil-Dependent Workers: Some developing nations (e.g., Nigeria, Indonesia) are reliant on fossil fuel extraction and exports. A just transition involves plans to retrain workers and diversify local economies away from this dependency.

- Affordability: Policies must ensure that the cost of the energy transition does not fall disproportionately on the poor. Tariff structures may need to be designed to protect the most vulnerable consumers.

Future Outlook and Key Takeaways

The future of renewable energy in developing nations is not a simple copy-paste of the developed world’s model. It is characterized by:

- Decentralization as the Default: For hundreds of millions, the first and only grid they will ever know will be a solar-powered mini-grid or a standalone home system.

- System Integration over Silos: The most successful approaches will integrate energy access with agriculture (solar water pumps), health (powering clinics), and education (digital learning).

- Resilience as a Driver: As climate change intensifies, the ability of decentralized renewables to withstand extreme weather and keep communities powered will become a critical advantage over vulnerable centralized grids.

- A New Geopolitical Dynamic: Developing nations are no longer mere recipients of aid but pivotal players in the global energy transition, holding the keys to both the problem (through potential emissions growth) and the solution (through critical minerals and vast renewable potential).