DNA Heredity Of course. Let’s break down the fascinating relationship between DNA and heredity. This is the core of how traits are passed from one generation to the next.

The Core Concept: The Blueprint of Life

- Think of DNA as the detailed, molecular instruction manual for building and running an organism. Heredity is the process of passing down that instruction manual from parents to offspring.

What is DNA?

- DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) is a molecule that contains the genetic code for all known life.

- Structure: It has a famous double-helix structure, like a twisted ladder.

- The sides of the ladder are made of sugar and phosphate.

- The rungs of the ladder are made of four chemical bases, called nucleotides: Adenine, Thymine, Cytosine, and Guanine.

- The Genetic Code: The specific order, or sequence, of these A, T, C, and G bases is the code. A sequence like ATTGCC is different from TTCGCA and holds different instructions.

- Genes: A gene is a specific, functional segment of DNA that provides the code for a specific protein or functional RNA molecule. It’s like a single “recipe” in the large instruction manual.

- Example: One gene might carry the instructions for making the protein keratin (for hair and nails), while another governs the production of digestive enzymes.

What is Heredity?

- Heredity (or inheritance) is the passing of traits from parents to their children. These traits can be physical (like eye color, height), behavioral, or related to susceptibility to certain diseases.

- How DNA Enables Heredity: The Step-by-Step Process

Here’s how DNA makes heredity possible, from one generation to the next.

Packaging DNA into Chromosomes

- Inside the nucleus of a cell, long DNA molecules are tightly coiled and packaged into structures called chromosomes. Humans have 46 chromosomes (23 pairs) in most cells.

Formation of Gametes (Sex Cells)

- Regular body cells (somatic cells) have two sets of chromosomes—one from each parent.

- To create sperm or egg cells (gametes), a special type of cell division called meiosis occurs.

- During meiosis, the chromosome pairs are separated, and each gamete ends up with only 23 chromosomes (one from each pair).

Fertilization

- When a sperm and an egg combine during fertilization, they create a single cell called a zygote.

- This zygote now has the full 46 chromosomes: 23 from the mother and 23 from the father. This restores the correct number and combines the genetic material from both parents.

Development and Expression of Traits

- The zygote divides over and over through mitosis, and every new cell in the developing offspring gets a complete copy of this combined DNA.

- The genes on these chromosomes are “read” by the cell’s machinery to produce proteins. The combination of proteins produced determines the traits of the offspring.

Key Principles of Heredity Explained by DNA

- The function of DNA perfectly explains the classical rules of heredity discovered by Gregor Mendel in the 19th century.

- Inheritance of Alleles: For any given gene, an individual inherits two alleles (one from each parent). These alleles are different versions of the same gene, located at the same spot on a pair of chromosomes.

- Example: The gene for eye color might have a “blue” allele and a “brown” allele.

Dominant and Recessive Traits:

- If you inherit a brown-eye allele from one parent, you will likely have brown eyes.

- To have blue eyes, you usually need to inherit a blue-eye allele from both parents.

- Genetic Variation: Why don’t siblings look identical (except for identical twins)?

- Crossing Over: During meiosis, chromosome pairs swap segments of DNA, creating new combinations of genes.

A Simple Analogy

- DNA is the entire instruction manual for building a house.

- A Chromosome is a chapter in that manual.

- A Gene is a single recipe or instruction set within that chapter (e.g., “how to build a window”).

- An Allele is a variation of that instruction (e.g., “bay window” vs. “double-hung window”).

- Heredity is the process of the construction company (the parents) giving a copy of their two instruction manuals to a new project manager (the child), who then uses the combined instructions to build a new, unique house.

The Central Dogma: From Code to Creature

This is the fundamental flow of genetic information that brings heredity to life:

DNA → RNA → Protein

- Replication (DNA → DNA): Before a cell divides, its entire DNA genome is copied. This ensures that each new cell (or each new offspring, via gametes) gets a complete set of instructions. This process is incredibly accurate but not perfect, which is where mutations (the source of new variation) can occur.

- This copy is not DNA, but a similar molecule called Messenger RNA (mRNA). Think of it as photocopying just one recipe page (the gene) from the massive instruction manual (the DNA) so you can take it to the kitchen without damaging the original book.

- Translation (RNA → Protein): The mRNA copy travels out of the cell’s nucleus to a ribosome (the cell’s “protein factory”). Each codon specifies a particular amino acid.

Why Proteins are Crucial: Proteins are the workhorses of the cell. They act as:

- Structural components (e.g., collagen in skin, keratin in hair).

- Enzymes that catalyze all chemical reactions in the body.

- Hormones that act as messengers.

- Receptors that receive signals.

- The trait you see (your phenotype) is ultimately the result of the proteins your genes produce.

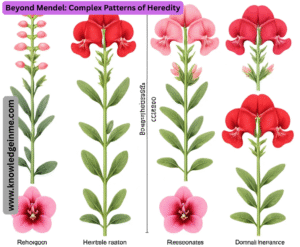

Beyond Mendel: Complex Patterns of Heredity

- Mendel’s work was foundational, but we now know that heredity is often more complex than simple dominant-recessive pairs.

- Incomplete Dominance: The heterozygote (mixed alleles) shows a blended phenotype.

- Example: A red snapdragon flower (RR) crossed with a white one (WW) produces pink offspring (RW).

- Codominance: Both alleles in the heterozygote are fully and separately expressed.

- Example: Blood type AB. The A allele codes for A markers on red blood cells, and the B allele codes for B markers. A person with both alleles has both markers present.

- Polygenic Inheritance: A single trait is controlled by multiple genes. This results in a continuous range of variation, like a bell curve.

- Example: Human height, skin color, and eye color. You don’t just have “tall” or “short” genes; you have combinations of many genes that each add a small amount to your overall height.

- Pleiotropy: A single gene influences multiple, seemingly unrelated traits.

- Example: Marfan syndrome is caused by a mutation in a single gene that affects connective tissue. This one gene can cause traits like unusually tall height, long fingers, and heart valve problems.

- Environmental Influence: Genes don’t operate in a vacuum. In humans, sunlight exposure influences skin color (a polygenic trait), and diet can influence height.

The Modern Connection: Genomics and Epigenetics

- Our understanding of heredity has exploded with new technology.

- Genomics: The study of the entire genome. We can now sequence all of an organism’s DNA. This allows us to:

- Identify genes associated with specific diseases.

- Understand evolutionary relationships at a molecular level.

- Trace human migration patterns by tracking hereditary markers in DNA.

- Epigenetics: This is a revolutionary field that studies changes in gene expression that do not involve changes to the underlying DNA sequence. Think of it as a layer of “software” on top of the DNA “hardware.”

- How it works: Chemical tags (like methyl groups) can attach to DNA or the proteins it wraps around (histones).

Real-World Applications

Understanding DNA heredity is not just academic; it’s critical to many fields:

- Medicine: Genetic testing for hereditary diseases like Huntington’s, BRCA1/2 (breast cancer), and cystic fibrosis. Pharmacogenomics tailors drugs to an individual’s genetic makeup.

- Forensics: DNA fingerprinting uses unique non-coding regions of DNA to identify individuals from crime scene evidence or determine paternity.

- Agriculture: Genetic engineering (GMOs) introduces desirable genes (like pest resistance) into crops. Selective breeding uses the principles of heredity to enhance livestock and plant yields.