Global Health Equity Of course. This is a critical and complex topic. Here is a comprehensive overview of Global Health Equity.

What is Global Health Equity?

Global Health Equity is the principle and pursuit of achieving the highest possible level of health and well-being for all people worldwide, regardless of their:

- Geographic location: Country, urban vs. rural.

- Socioeconomic status: Income, wealth, occupation.

- Demographics: Race, ethnicity, gender, age, sexual orientation.

- Social identity: Disability, religion, political belief.

- It is fundamentally a matter of social justice. The core idea is that everyone should have a fair and just opportunity to be healthy. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and lack of access to education, safe environments, and healthcare.

Key Concepts: Equity vs. Equality

- This is the most crucial distinction to understand:

- Equality: Giving everyone the exact same thing.

The Classic Illustration:

- Imagine a short person, a medium-height person, and a tall person trying to watch a baseball game over a fence.

- Equality would be giving each person the same one-box to stand on. The tall person can see fine, the medium person can see a little, but the short person still can’t see the game. The outcome is not fair.

- Equity would be giving the tall person no box, the medium person one box, and the short person two boxes. Now, everyone can see over the fence. The outcome is fair because resources were distributed based on need.

- In global health, this means directing more resources, attention, and tailored interventions to the populations and countries that are most disadvantaged.

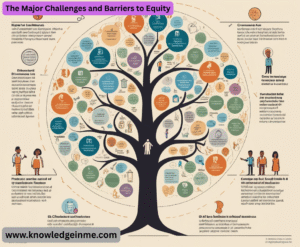

The Major Challenges and Barriers to Equity

- The disparities in health outcomes are driven by deep-rooted, systemic factors known as the Social Determinants of Health (S D O H).

- Poverty and Economic Inequality: This is the single biggest driver. Poverty limits access to nutritious food, clean water, safe housing, and healthcare.

- Political and Social Injustice: Conflict, corruption, weak governance, and discrimination (racism, sexism, xenophobia) systematically disadvantage certain groups.

- Geographic Disparities: There is a vast gap in health outcomes and life expectancy between high-income and low-income countries, and between urban and rural areas within countries.

- Lack of Access to Healthcare: This includes not just the physical absence of clinics and hospitals, but also the inability to afford care, a shortage of trained health workers, and poor-quality services.

- Educational Disparities: Lower levels of education, particularly for women and girls, are strongly correlated with poorer health outcomes.

- Environmental Factors: Populations in low-resource settings often bear the brunt of environmental degradation, pollution, and the impacts of climate change, while contributing the least to the problem.

Real-World Examples of Health Inequity

- Maternal Mortality: A woman in sub-Saharan Africa is nearly 50 times more likely to die during childbirth than a woman in a high-income country. This is not due to biology, but to lack of access to skilled birth attendants, emergency obstetric care, and family planning.

- Vaccine Access: During the COVID-19 pandemic, high-income countries hoarded vaccines, while many low-income countries waited months or years for sufficient doses. This “vaccine apartheid” prolonged the pandemic and allowed new variants to emerge.

- Burden of Infectious Diseases: Diseases like Malaria, Tuberculosis, and HIV/AIDS disproportionately affect the poorest regions of the world (e.g., Africa and Southeast Asia), where prevention and treatment resources are scarce.

- The “Brain Drain”: Many low- and middle-income countries invest in training doctors and nurses, only to see them migrate to higher-paying jobs in wealthier nations, crippling their own health systems.

Strategies for Achieving Global Health Equity

- Achieving equity requires multi-faceted, long-term strategies that go far beyond just building clinics.

- Strengthening Health Systems: Investing in robust, publicly-funded primary healthcare that is accessible, affordable, and of high quality for everyone, especially the most vulnerable.

- Addressing Social Determinants: Tackling the root causes by advocating for policies that reduce poverty, improve education, ensure food security, and provide clean water and sanitation.

- Promoting Community-Led Solutions: Empowering local communities to identify their own health priorities and be partners in designing and implementing interventions. This ensures cultural relevance and sustainability.

- Global Governance and Financing: Reforming international systems to be more equitable. This includes supporting organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) and creating fairer mechanisms for financing health in low-income countries (e.g., The Global Fund).

- Data Equity: Improving the collection and use of dis aggregated data (by income, gender, race, location, etc.) to identify disparities and target interventions effectively. You can’t fix what you don’t measure.

- Decolonizing Global Health: Challenging the power imbalances where high-income countries set the agenda and control the funding for health in low-income countries. This involves shifting power, resources, and leadership to local institutions.

Key Organizations Working on Global Health Equity

- World Health Organization (WHO): The leading UN agency.

- The Global Fund: A financing institution to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.

- Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: Works on vaccine equity.

- Partners In Health (P I H): A non-profit known for its social justice approach to delivering healthcare in poor communities.

- Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières): Provides emergency medical care in crisis situations.

Beyond the Basics: Deepening the Understanding

The Conceptual Frameworks

- Understanding global health equity is guided by several key frameworks:

- The Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Model (WHO): This is the foundational model that categorizes the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. The model includes:

- Structural Determinants: The socioeconomic and political context (e.g., governance, policies, social norms).

- Intermediary Determinants: Material circumstances (housing, food), psychosocial factors, behavioral and biological factors, and the health system itself.

- Structural Violence: A concept coined by Johan Galtung and popularized in medical anthropology by Paul Farmer. It refers to how social structures (economic, political, legal, religious, and cultural) can cause harm to individuals by preventing them from meeting their basic needs. For example, a racist housing policy that leads to overcrowded slums is a form of structural violence that results in higher rates of tuberculosis. It’s “violence” that is built into the structure and shows up as unequal power and life chances.

- Intersectionality: Originally developed by Kimberlé Crenshaw, this concept is crucial for equity. It posits that people are often disadvantaged by multiple sources of oppression: their race, class, gender identity, sexual orientation, religion, and other identity markers. These factors intersect and create overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage. A poor, indigenous woman will face compounded barriers to health that a poor man or a wealthy woman from the same community may not.

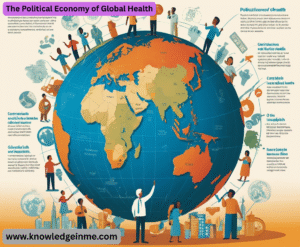

The Political Economy of Global Health

This examines how political and economic structures and ideologies create and perpetuate health inequities.

- Power Imbalances: Global health is often characterized by a top-down flow of resources and agenda-setting from high-income countries (HICs) and private foundations in the Global North to low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global South. This can undermine local sovereignty and priorities.

- Intellectual Property and Trade Laws: Agreements like TRIPS (Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights) allow pharmaceutical companies to patent drugs for decades, making life-saving medications unaffordable for the world’s poor. The struggle for access to HIV/AIDS medications in the 2000s and COVID-19 vaccines more recently are prime examples.

- Debt and Structural Adjustment: In the late 20th century, International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank structural adjustment programs forced LMICs to cut public spending on health and education to repay debts, crippling their health systems for a generation.

Key Tensions and Critical Debates

Vertical vs. Horizontal Funding:

- Vertical Programs: Disease-specific initiatives (e.g., only for malaria or HIV). They are often well-funded and can show quick results but can weaken the general health system by creating parallel structures and diverting health workers.

- Horizontal Programs: Funding aimed at strengthening the entire health system (e.g., training health workers, building supply chains, supporting primary care). This is essential for long-term equity but is often less attractive to donors who want measurable, short-term impact.

- The Ideal: A “diagonal” approach that uses strategic vertical investments to strengthen the overall horizontal system.

- Decolonizing Global Health: This is a major, evolving movement. It argues that the field is still rooted in colonial-era power dynamics and mindsets. Key demands include:

- Shifting Power and Leadership: Moving decision-making and funding control from HICs to LMICs.

- Addressing “White Savior” Complex: Challenging narratives that portray people in the Global South as helpless victims and HIC actors as saviors.

- Reforming Academic Partnerships: Ensuring that research collaborations are truly equitable, with LMIC researchers as lead investigators, not just data collectors, and that findings are translated into local benefit.

- The Rise of Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs): While the traditional focus has been on infectious diseases, NCDs like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes are now the leading cause of death globally, with the fastest growth in LMICs. This creates a “double burden” of disease and exposes populations to unhealthy commodities (e.g., ultra-processed foods, tobacco, alcohol) aggressively marketed by multinational corporations. Addressing this requires a focus on commercial determinants of health.

Measuring Equity

- You can’t manage what you don’t measure. Key methods include:

- Disaggregated Data: Breaking down health data by income, gender, ethnicity, geography, etc., to uncover hidden disparities. For instance, a national average for vaccination coverage might mask very low rates for a specific ethnic minority.

- Equity-Focused Targets: Moving beyond national averages. For example, a goal might be “reduce neonatal mortality to 12 per 1000 live births and ensure that the gap between the richest and poorest quintiles is reduced by half.”

- Concentration Index and Wealth Quintiles: Statistical tools used to measure the degree of income-related inequality in a health variable.