Expository At its core, expository writing is informational writing. Its primary purpose is to explain, describe, or inform a reader about a specific topic, process, or idea. The word “expository” comes from the verb “to expose,” but not in the sense of revealing a scandal. Instead, it means to “expose” or “lay out” information in a clear, logical, and factual manner. Unlike persuasive writing, which aims to convince, or narrative writing, which tells a story, expository writing is grounded in facts, evidence, and objectivity. It is the backbone of most of the informative text we encounter in our daily lives.

The Key Characteristics of Expository Writing

Effective expository writing is defined by several key traits:

- Clarity and Conciseness: The language is straightforward and easy to understand. It avoids unnecessary jargon and florid language, prioritizing the clear communication of ideas.

- Factual and Evidence-Based: The writing is built on a foundation of reliable facts, statistics, examples, and data. It does not rely on personal opinion or emotional appeals.

- Organized and Logical Structure: Information is presented in a structured format. This often includes a clear thesis statement, well-organized paragraphs with topic sentences, and smooth transitions that guide the reader from one point to the next.

- Impartial and Objective Tone: The writer’s goal is to inform, not to persuade. The tone remains neutral and unbiased, presenting information fairly without injecting personal feelings.

- Thesis-Driven: A strong expository piece is centered around a main idea or thesis statement. This central claim is then supported and elaborated upon throughout the text.

Common Structures (or Modes) of Exposition

Writers don’t just present facts randomly; they organize them using specific structural patterns. Here are the most common types of expository writing:

- Compare and Contrast: This structure examines the similarities and differences between two or more subjects (e.g., comparing democracy and monarchy, or contrasting two novels by the same author).

- Cause and Effect: This pattern explains the reasons (causes) for an event or situation and the results (effects) that follow (e.g., explaining the causes of the Great Depression and its effects on society).

- Process (How-To): Also known as “sequential” writing, this explains how something is done or how something works through a series of steps (e.g., a recipe, a manual for assembling furniture, or an explanation of how a bill becomes a law).

- Problem and Solution: This structure identifies a problem and then proposes one or more potential solutions (e.g., an essay discussing the problem of plastic pollution in oceans and proposing legislative and consumer-based solutions).

- Definition: This mode explores the meaning of a complex concept, term, or idea by detailing its characteristics, history, and context (e.g., defining “artificial intelligence” or “social justice”).

- Classification: This pattern breaks a broad subject down into categories and subcategories to help the reader understand it better (e.g., classifying types of rock music, government systems, or literary genres).

Where You Encounter Expository Writing

Expository writing is everywhere. You interact with it constantly, often without even realizing it. Common examples include:

- Academic Texts: Textbooks, research papers, essays, and lab reports.

- News Articles: Newspaper and magazine articles that report on events (the “who, what, when, where, why, and how”).

- Non-Fiction Books: Books about history, science, biography, and other factual topics.

- Technical and Business Writing: Instruction manuals, whitepapers, reports, and memos.

- Encyclopedia Entries: Articles on Wikipedia or in traditional encyclopedias.

- How-To Guides and Recipes: Instructions for completing a task.

The Expository Engine How It Works in Practice

- Think of an expository piece as a machine designed for understanding. Every part has a specific function.

The Thesis Statement: The Blueprint

- The thesis statement is the single most important sentence in an expository essay. It acts as the blueprint, telling the reader exactly what to expect.

- It states the topic: What are you explaining?

- It makes a specific claim: What is the key point about this topic?

- It often hints at the structure: How will you prove your point?

- Weak Thesis: “This essay is about social media.” (Too vague)

- Strong Thesis: “While often criticized for isolation, social media platforms have fundamentally reshaped social activism by enabling rapid information dissemination and global community building.” (This is specific, debatable-in-a-factual-way, and sets up a compare/contrast or cause/effect structure).

The Supporting Paragraphs: The Framework

- Each paragraph should be a mini-essay that supports the main thesis.

- Topic Sentence: The first sentence of the paragraph should state the single point of that paragraph, which directly supports the thesis.

- Evidence and Examples: This is the “proof.” It includes facts, statistics, quotes from experts, anecdotes, or concrete examples. A paragraph on “rapid information dissemination” might cite the speed at which news about a natural disaster spreads on Twitter.

- Analysis and Explanation: Don’t just drop a fact and move on. Explain how that fact supports the paragraph’s point and the overall thesis. Connect the dots for the reader.

- Concluding/Transition Sentence: Wrap up the paragraph’s idea and smoothly lead into the next point.

The Conclusion: The Final Inspection

- The conclusion does not simply repeat the thesis. It synthesizes the information.

- Restate the Thesis in a New Way: Rephrase your main argument based on the evidence you’ve presented.

- Summarize Key Points: Briefly recap the main supporting arguments from your body paragraphs.

- Provide a Final Insight: Discuss the broader significance, implications, or future outlook of the topic. Answer the question, “So what?”

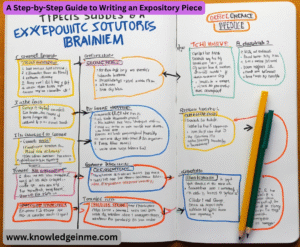

A Step-by-Step Guide to Writing an Expository Piece

- Pre-Write and Brainstorm: Choose your topic and use techniques like mind-mapping or listing to generate ideas. Decide which expository structure (compare/contrast, cause/effect, etc.) best fits your purpose.

- Research: Gather factual information from credible sources (academic journals, reputable news outlets, government websites, expert interviews). Take notes and track your sources.

- Craft a Strong Thesis: Based on your research, write a clear, specific thesis statement that will guide your entire essay.

- Create an Outline: Organize your main points and supporting evidence into a logical sequence. This is your roadmap and prevents your essay from becoming disorganized.

Write the First Draft:

- Introduction: Start with a “hook” to grab the reader’s interest (a surprising fact, a compelling question, a brief story). Provide context and end with your thesis statement.

- Body Paragraphs: Follow your outline, ensuring each paragraph has a topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- Conclusion: Synthesize your argument without introducing new information.

- Revise and Edit: This is a multi-step process.

- Revise for Content: Look at the “big picture.” Is the argument clear? Is the organization logical? Is there enough evidence? Do you need to cut or add anything?

- Edit for Clarity and Style: Check sentence flow, word choice, and transition words. Read it aloud to catch awkward phrasing.

- Proofread: Correct grammar, spelling, and punctuation errors. A sloppy presentation undermines your credibility.

Advanced Nuances: What Makes Expository Writing Excellent?

- Knowing Your Audience: The way you explain a complex topic to a group of experts will be different from how you explain it to a general audience. Excellent expository writing tailors its language and depth to the reader.

- Maintaining Objectivity vs. Voice: While expository writing is factual, it doesn’t have to be robotic. A distinct “voice”—clear, professional, and engaging—can make the information more palatable. The key is to let the evidence lead, not your personal feelings.

- The Power of Transitions: Words and phrases like “furthermore,” “consequently,” “on the other hand,” and “for example” are the glue that holds an expository piece together. They create a seamless flow, guiding the reader through your logical progression.

- Addressing Counter-arguments: In more advanced expository writing (like a research paper), it strengthens your credibility to acknowledge other perspectives or counter-arguments. You can then explain, with evidence, why your explanation is more accurate or comprehensive. This demonstrates thorough research and critical thinking.