Autistic Masking Of course. This is a crucial and often misunderstood topic. Let’s break down what autistic masking is, why it happens, its profound consequences, and the path toward “unmasking.”

What is Autistic Masking?

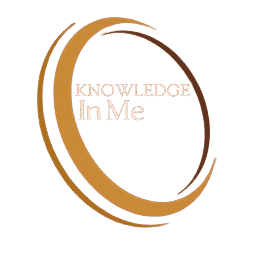

- Autistic masking (also known as camouflaging) is the conscious or subconscious suppression of natural autistic behaviors and the replication of neurotypical ones to fit in and navigate a world primarily designed for non-autistic people.

- Think of it as a “social survival strategy.” It involves constantly monitoring and adjusting one’s behavior, presentation, and communication to appear less autistic.

Common Masking Behaviors Include:

- Forcing Eye Contact: Maintaining eye contact even when it is physically painful or overwhelming, and focusing so much on how to do it that you miss the conversation.

- Scripting Conversations: Pre-planning phrases, jokes, or entire conversations for common social situations. Relying on “scripts” from TV, movies, or observed interactions.

- Suppressing Stims: Hiding self-stimulating behaviors (stimming) like hand-flapping, rocking, or vocalizations, which are natural ways for autistic people to regulate emotions and sensory input. This can be replaced with a more “socially acceptable” but less effective stim, like jiggling a foot under a table.

- Imitating Social Cues: Copying the tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language of others, often from characters or people they know. This can feel like performing a role.

- Hiding Special Interests: Not talking about passionate, deep interests for fear of being seen as “too much” or “weird,” and instead forcing small talk.

- Pushing Through Sensory Overload: Enduring overwhelming sensory environments (bright lights, loud noises, strong smells) without using coping tools like noise-canceling headphones or sunglasses to avoid drawing attention.

Why Do Autistic People Mask?

The reasons are complex and often rooted in a need for safety and belonging:

- Social Acceptance & Fitting In: The most common reason. From a young age, many autistic people are explicitly or implicitly taught that their natural ways of being are “wrong” or “annoying.” Masking is a way to avoid bullying, rejection, and social isolation.

- Professional Survival: To get and keep a job, navigate workplace social politics, and appear “professional,” which often means conforming to neurotypical standards of communication and behavior.

- Safety: For many, particularly women, girls, and gender-diverse individuals, masking is a safety mechanism to avoid standing out and becoming a target for harassment or violence.

- Internalized Stigma: After a lifetime of being told they are “too loud,” “too quiet,” “too intense,” or “inappropriate,” an autistic person may internalize these messages and believe they need to mask to be likable or worthy.

The Profound Consequences of Masking

- While masking can offer short-term benefits (like social acceptance), the long-term costs are severe. It is an exhausting, cognitively demanding process that comes at a great expense to mental health.

- Autistic Burnout: This is a state of intense physical, mental, and emotional exhaustion. It often includes a loss of skills, increased sensitivity to stimuli, and debilitating fatigue. It’s the direct result of the prolonged stress of trying to navigate a world not designed for you, with masking being a major contributor.

- Identity Loss & Depersonalization: After masking for so long, a person can lose touch with who they truly are. They may not know their own preferences, boundaries, or personality outside of the “mask.”

- Mental Health Crises: The constant effort and internal dissonance are strongly linked to:

Anxiety and depression

Suicidal ideation

Poor self-esteem and self-worth

- Delayed or Missed Diagnosis: Many individuals, especially those socialized as female, become so adept at masking that their autistic traits are not recognized by professionals, leading to a late diagnosis or misdiagnosis (e.g., with anxiety or borderline personality disorder).

- The “You Don’t Look Autistic” Paradox: When an autistic person masks effectively, they are often met with disbelief when they disclose their diagnosis, which further invalidates their experience.

Unmasking: The Path to an Authentic Life

- “Unmasking” is the process of consciously letting go of masking behaviors and rediscovering and embracing one’s authentic autistic self. It is a journey, not a destination, and requires immense courage and a safe environment.

- How to Support Unmasking:

- For Autistic Individuals:

- Start Small & Safe: Begin by unmasking in a safe, low-demand environment, either alone or with a trusted person.

- Reconnect with Your Body: Allow yourself to stim freely. Pay attention to sensory needs (e.g., wear comfortable clothes, use sensory tools).

- Identify Your Needs: Ask yourself, “What do I need right now?” without judging the answer.

- Explore Special Interests: Re-engage with your passions without shame.

- Set Boundaries: Learn to say “no” to social events or environments that are draining.

- Seek Community: Connect with other autistic people (online or in person). This is one of the most powerful steps, as it provides validation and models for authentic living.

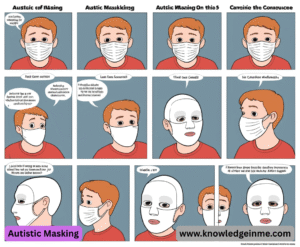

For Allies, Friends, and Family:

- Educate Yourself: Understand that masking is real and draining.

- Create a Safe Space: Explicitly state that it’s okay to be authentic. “You don’t have to make eye contact with me if it’s hard,” or “I love hearing about your special interests.”

- Believe Them: If someone tells you they are autistic, believe them without question. Don’t say, “But you seem so normal!”

- Reduce Social Demands: Don’t pressure them to attend events. Offer low-pressure ways to connect.

- Validate Their Experience: Acknowledge the effort they put into navigating the world.

The “How” of Masking: The Cognitive Machinery

- Masking isn’t just a decision; it’s a complex, resource-intensive cognitive process. It often relies on:

- Analytical Observation & Pattern Recognition: Many autistic people are hyper-observant. They become amateur ethnographers, meticulously studying neurotypical social rules, body language, and conversational rhythms. They deconstruct social interactions into a set of patterns and rules that they can then attempt to replicate.

- Constant Predictive Modeling: The brain runs a continuous simulation: “If I say X, they will likely respond with Y. I should then counter with Z. I need to remember to nod here and make eye contact for approximately 2 seconds.” This is a form of systemizing social interaction.

- Executive Function Overload: Masking places an enormous demand on the brain’s executive functions: working memory (holding the script in mind), inhibitory control (suppressing stims and unfiltered thoughts), and cognitive flexibility (switching between your natural state and the masked performance). This is why masking is so mentally exhausting.

The Many Faces of Masking: It’s Not One-Size-Fits-All

- Masking manifests differently across individuals and contexts, influenced by factors like gender, age, and co-occurring conditions.

- Gender & Socialization:

- Women, Girls, and Gender-Diverse Individuals: Often socialized to be more relational and compliant, they may develop more “advanced” masking techniques. Their masking can be more focused on imitating social nuance, fostering friendships, and being “pleasing,” which is why they are frequently misdiagnosed or diagnosed later in life.

- Men and Boys: While also masking, their camouflage might manifest differently, perhaps as forcing a stoic demeanor, mimicking “locker room talk,” or suppressing emotions more intensely to conform to masculine norms.

- The “High-Masking” Autistic Profile: This describes individuals whose coping strategy is predominantly masking. They may have:

Fewer external autistic traits visible to others.

- A high likelihood of anxiety, depression, and exhaustion.

- Exceptional cognitive abilities that they’ve leveraged to build their “mask.”

- A profound sense of being an imposter in both neurotypical and autistic spaces.