The Obesity Era by David Berreby Of course. David Berreby’s essay “The Obesity Era,” originally published in Aeon and later featured in The Best American Science. Nature Writing 2014, is a profound and influential critique of the standard narrative about the causes of the global obesity crisis. Here is a comprehensive summary and analysis of its key arguments.

The Core Thesis

Berreby’s central argument is that the conventional explanation for the obesity epidemic—”people eat too much and exercise too little“—is dangerously simplistic and scientifically inadequate. He posits that the true causes are far more complex, systemic, and embedded in our modern environment, particularly in the form of industrial chemicals and environmental “obesogens.”

Summary of Key Arguments

- Berreby structures his essay to dismantle the personal-responsibility model and build a case for an environmental one.

The Failure of the “Gluttony and Sloth” Model:

- He points out that the obesity epidemic has occurred across all demographics, ages, and even in family pets and laboratory animals, which share our environment but not our diets or lifestyles. This suggests a common, pervasive environmental trigger.

- The standard model fails to explain why obesity rates continued to skyrocket even as public awareness of diet and exercise reached an all-time high.

The Role of Viruses and Microbiome:

- Berreby discusses the work of researchers like Nikhil Dhurandhar, who found that a specific virus (adenovirus-36) could cause animals to gain significant fat. This introduced the idea that obesity could have an infectious component.

- He also touches on the gut microbiome, suggesting that the balance of bacteria in our digestive systems, influenced by modern antibiotics and diets, can affect how we extract and store energy from food.

The Main Culprit: Environmental “Obesogens”:

- This is the heart of Berreby’s argument. He delves into the research of scientists like Bruce Blumberg, who coined the term “obesogen.”

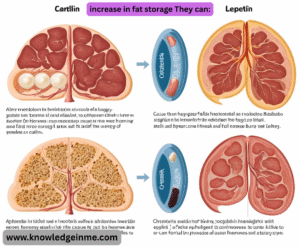

- Obesogens are chemical compounds that disrupt the normal functioning of the endocrine (hormone) system, leading to an

increase in fat storage They can:

- Promote Fat Cell Proliferation: Cause stem cells to turn into fat cells.

- Alter Metabolism: Change the body’s metabolic “set point,” making it more likely to store calories as fat and harder to burn fat for energy.

- Disrupt Appetite Signals: Interfere with hormones like leptin and ghrelin that regulate hunger and satiety.

Examples of suspected obesogens include:

- Tributyltin (TBT): Used in marine paints and plastics.

- Bisphenol A (BPA): Found in many plastics and food can linings.

- Phthalates: Found in plastics, cosmetics, and fragrances.

Pesticides and herbicides: Like Atrazine.

- Air Pollution: Fine particulate matter has been linked to weight gain and metabolic issues.

An Evolutionary and Systemic Problem:

- Berreby argues that our bodies’ ancient, fat-storing mechanisms are being hijacked by a modern chemical environment they never evolved to handle.

- The problem is not a simple lack of willpower but a fundamental mismatch between our biology and the industrialized world we have created. The food industry’s highly processed, calorie-dense foods are the “vehicle,” but the obesogens are a key “driver” of the dysregulation that leads to weight gain.

Significance and Implications

“The Obesity Era” was significant because it:

- Challenged Stigma: It provided a scientific basis for arguing that obesity is not primarily a moral failing but a physiological condition induced by a toxic environment. This helps combat the widespread stigma and shame associated with being overweight.

- Shifted the Blame: It moved the focus from individual choices to powerful systemic factors, including industrial agriculture, chemical manufacturing, and the food industry.

- Called for a New Approach: Berreby implies that public health solutions focused solely on calorie counting and exercise are doomed to fail. Instead, we need to regulate and remove harmful chemicals from our environment and food supply.

Criticisms and Counterpoints

- While highly influential, the essay’s arguments are part of an ongoing scientific debate:

- Correlation vs. Causation: Some critics argue that the evidence for obesogens in humans is still largely correlational and not yet definitively proven to be a primary cause of the epidemic.

- Complexity of Solutions: Even if obesogens are a major cause, regulating thousands of industrial chemicals is a monumental political and economic challenge.

The Attack on “Just-So Stories” and Moralizing:

- Berreby is fundamentally critiquing what he sees as a comforting but false narrative. The “eat less, move more” story is simple, places blame on the individual, and aligns with deep-seated cultural notions of sin and virtue. He argues that we cling to this story because the alternative—that we are being passively altered by invisible chemicals—is far more frightening and difficult to address.

- He uses the rhetorical strategy of “defamiliarization.” By pointing out that lab rats, feral rats, and house pets are also getting fatter, he makes the familiar strange. This forces the reader to see that something must be wrong with our initial assumption. If these animals aren’t making poorlifestyle choices, what are they (and we) experiencing?

The Shift from “Energy Balance” to “Biological Regulation”:

- The conventional model is based on a simple physics equation: Calories In > Calories Out = Weight Gain.

- Berreby’s obesogen theory replaces this with a biological model of dysregulation. It’s not about the sheer number of calories, but about how the body manages those calories. Do they get burned for energy, or stored as fat? What is the body’s “set point” for weight? Obesogens, he argues, corrupt the software (the endocrine system) that runs the body’s energy-management hardware.

- This is a profound shift. It moves the problem from a matter of arithmetic to a matter of endocrinology and developmental biology.

The “First Plastics” Generation Hypothesis:

- While not explicitly stated as a single section, the essay heavily implies a critical historical turning point. The post-World War II explosion in the production of synthetic chemicals—plastics, pesticides, herbicides, and industrial compounds—created a new environmental exposure.

- The essay suggests that we are living through a massive, unplanned, and uncontrolled experiment on human physiology. The “Obesity Era” began when the first generation exposed to high levels of these chemicals in the womb and infancy reached adulthood, passing on altered metabolic tendencies.

Expanding on the Science: Key Concepts Mentioned

Let’s flesh out the scientific mechanisms Berreby highlights:

- Adenovirus-36: This research suggests that an infection could “switch on” genes that promote fat cell creation and accumulation. It’s a powerful example of how a non-dietary, environmental agent can directly cause obesity.

- The Gut Microbiome: The essay touches on how modern diets (high in fat/sugar, low in fiber) and antibiotic use have altered the ecosystem of our guts. Some bacterial profiles are more efficient at extracting energy from food, meaning two people eating the same apple might absorb different amounts of calories from it.

- The Thrifty Gene Hypothesis (and its critique): Berreby implicitly challenges the popular idea that obesity is caused by our genes being adapted for famine. While evolutionary pressure plays a role, he argues it’s insufficient to explain the sudden, global spike. The obesogen theory provides the “environmental trigger” that activates these genetic predispositions.