Science and medicine Of course! “Science and medicine” is a vast and profoundly interconnected field. It’s the engine that drives our understanding of the human body, the development of new treatments, and the improvement of public health. At its core, this relationship is a continuous cycle: Basic Science (The “Why”) → Translational Research (The “How”) → Clinical Medicine (The “Application”) → New Questions → Back to Basic Science Let’s break down the key areas and their interplay.

The Foundational Sciences for Medicine

Modern medicine rests on a bedrock of scientific disciplines:

- Biology & Genetics: Understanding life at every level, from cells to ecosystems. The discovery of DNA’s structure revolutionized medicine, leading to genetic testing, gene therapies (like for certain cancers), and personalized medicine.

- Chemistry & Biochemistry: The study of matter and the chemical processes within living organisms. This is crucial for drug design, understanding metabolic pathways, and developing diagnostic assays.

- Physics: Provides the tools for medical imaging (X-rays, MRI, CT scans, ultrasound) and radiation therapy for cancer.

- Biostatistics & Epidemiology: The science of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data to understand disease patterns in populations. This is the foundation of public health policy and clinical trials.

Key Interdisciplinary Fields

This is where the lines between “pure science” and “medicine” blur:

- Immunology: The study of the immune system. It has been central to developing vaccines (from smallpox to COVID-19), understanding allergies, and creating revolutionary treatments for autoimmune diseases and cancer (immunotherapy).

- Neuroscience: The study of the nervous system. It seeks to understand the brain, leading to better treatments for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, depression, and spinal cord injuries.

- Oncology: The study of cancer. It combines genetics, cell biology, and immunology to develop targeted therapies that are more effective and less toxic than traditional chemotherapy.

- Pharmacology: The study of drug action. It determines how chemicals interact with biological systems to create new medications and optimize their use.

- Bioengineering & Biotechnology: Applying engineering principles to medicine. This leads to creations like artificial organs, prosthetics, advanced biomaterials, and the mRNA vaccine technology.

The Process: From Lab Bench to Bedside

This is the “translational” pipeline:

- Basic Discovery: A scientist in a lab discovers a novel cellular mechanism or a new protein involved in a disease.

- Preclinical Research: The discovery is tested in cell cultures and animal models to see if it can be modified into a potential treatment.

- Clinical Trials: If safe and effective in preclinical models, the treatment is tested in human volunteers in phased trials (Phase I-III) to assess safety, dosage, and efficacy.

- Regulatory Approval: Government agencies (like the FDA in the US) review the trial data and decide whether to approve the treatment for public use.

- Clinical Implementation & Monitoring: Doctors prescribe the new treatment, and ongoing surveillance (Phase IV trials) monitors its long-term effects in the general population.

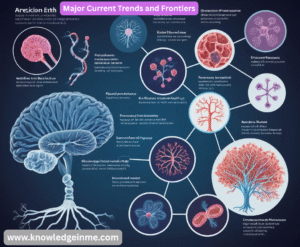

Major Current Trends and Frontiers

The field is evolving at an incredible pace:

- Precision & Personalized Medicine: Moving away from “one-size-fits-all” treatments. Using a patient’s genetic makeup, lifestyle, and environment to tailor prevention and treatment strategies.

- Genomics and Gene Editing: Sequencing the entire human genome is now routine. Technologies like CRISPR allow scientists to edit genes with high precision, offering potential cures for genetic disorders.

- AI and Machine Learning: AI is being used to analyze medical images (e.g., detecting tumors on radiology scans), discover new drugs, predict disease outbreaks, and personalize treatment plans.

- Microbiome Research: Understanding the vast ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, and fungi living in and on us, and how it influences our health, from digestion to mental health.

- Telemedicine and Digital Health: Using technology to provide remote care, monitor patients’ health in real-time, and increase access to medical expertise.

- mRNA Technology: Proven by the COVID-19 vaccines, this platform allows for rapid development of vaccines and therapies for a wide range of diseases.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

The advancement of science and medicine also brings complex challenges:

- Cost and Accessibility: Cutting-edge treatments are often extremely expensive, raising questions about equitable access.

- Ethics of Genetic Engineering: Where do we draw the line with editing human genes, especially in the germline (heritable changes)?

- Data Privacy: The use of AI and vast amounts of patient data raises serious concerns about privacy and security.

- Misinformation: The spread of false or misleading health information can undermine public trust and health outcomes.

The Unspoken Backbone: The Scientific Method in the Clinic

- At its heart, modern medicine is the application of the scientific method to a single patient. This process is called Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM).

- Observation & Question: A patient presents with a set of symptoms (Observation). The doctor asks: “What is the underlying cause, and what is the best treatment?” (Question).

- Hypothesis: The doctor forms a differential diagnosis—a list of potential hypotheses (e.g., “It could be condition A, B, or C”).

- Experimentation (Testing): This is the diagnostic process. They order lab tests, imaging, and biopsies to gather data.

- Analysis: The doctor interprets the test results against the initial hypotheses.

- Conclusion (Diagnosis & Treatment Plan): A diagnosis is reached, and a treatment plan based on the best available scientific evidence is implemented.

- This cycle continues as the patient’s response to treatment provides new data, potentially leading to a revised hypothesis and plan.

The Cutting Edge: A Closer Look at Emerging Frontiers

Let’s expand on a few of the trends mentioned earlier.

Precision Oncology: A Cancer Case Study

- This is perhaps the best example of the science-medicine pipeline in action today.

- The Science: Genomic sequencing of cancer cells reveals that a lung tumor has a specific mutation in the EGFR gene.

- The Translation: Scientists develop a drug (a small-molecule inhibitor) that is designed to precisely block the protein produced by the mutated EGFR gene.

- The Medicine: Instead of giving the patient standard chemotherapy (which attacks all rapidly dividing cells), the oncologist prescribes the targeted therapy. The pill specifically tells the cancer cells to stop dividing, often with fewer side effects.

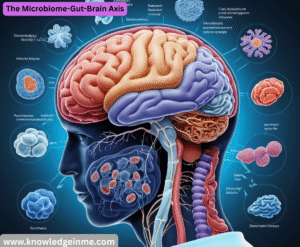

The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis

This is a frontier reshaping our understanding of whole-body health.

- The Science: Research shows that the community of bacteria in your gut (the microbiome) produces neurotransmitters and inflammatory molecules that can signal the brain via the vagus nerve.

- The Medical Implications: This is leading to novel investigations into using probiotics, prebiotics, and even fecal microbiota transplants to potentially help manage conditions like depression, anxiety, Parkinson’s disease, and autoimmune disorders. It’s linking fields that were once separate: gastroenterology, psychiatry, and neurology.

The AI Revolution: From Diagnosis to Drug Discovery

- In Diagnostics: AI algorithms are now outperforming humans in detecting certain diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy from eye scans or subtle breast cancers on mammograms. They act as a powerful “second opinion.”

- In Drug Discovery: AI can analyze vast databases of molecular structures to predict which compounds might effectively target a disease-related protein, slashing the time and cost of the initial discovery phase from years to months.

The Inherent Tensions and Ethical Dilemmas

- The marriage of science and medicine is not always smooth. It exists within a complex framework of ethical, economic, and social challenges.

- The Art vs. The Algorithm: Medicine is not just applied science. The art of medicine involves empathy, communication, understanding a patient’s values, and dealing with uncertainty. An over-reliance on data can dehumanize care. How do we balance a statistically effective treatment with what is right for this specific person?

- The Commercialization of Health: Scientific research is expensive. Pharmaceutical and biotech companies drive much innovation but also create high drug prices and can influence research agendas towards profitable, rather than necessarily the most needed, areas.

- Informed Consent in the Genomic Age: If you have your genome sequenced for one reason, who owns that data? What if it reveals a high risk for an untreatable disease? Do doctors have an obligation to tell you? Do your family members have a right to know?

- Equity and Access: The benefits of high-tech, science-driven medicine are often concentrated in wealthy nations and communities. This creates a global “health gap.” How do we ensure that a gene therapy costing millions of dollars becomes accessible to all who need it?